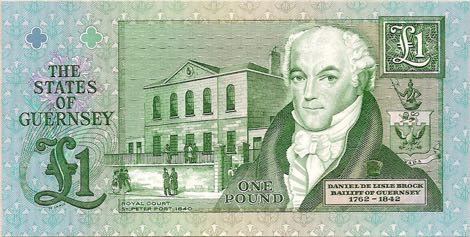

Ask visitors what they think makes Guernsey unusual if not unique, and the answer is likely to be the cows, hedge veg…and the £1 notes. Ah, those £1 notes – quaint crinkly green pieces of paper which you rarely see new and which seem to age rather well.

You don’t have to know the answer to the tricky question “What is money?” to realise that these days it means more than cold hard cash. But given that we’re talking here about notes and coins, let’s overlook this complication.

Let’s also put aside the fact that governments used to issue only as much cash as they had in (typically) gold. That is a complication too. The last government which promised to give you gold for your cash was the US, at the rate of $35 an ounce.

All we really need to know is that practically all the currency issued by governments these days is ‘fiat’ money, that is, unbacked. The UK pound sterling, before it became a coin, promised to the “pay the Bearer on demand” if the holder went to the Bank of England which had issued it in the first place. But if anyone did that, the holder of the note would probably receive another in its place.

The same is true with the States of Guernsey, the island’s currency issuer. What is different, though, is that Guernsey does not retain any gold or foreign exchange reserves to back its currency. Some people think that the amounts issued are first matched with sterling pounds collected in the island. Not so.

No less interesting, the States actually profits from the currency’s issue. First it contracts with a UK currency manufacturer like De La Rue (an appropriate Guernsey name). It gives a mound of notes (say £1 million face value) to a local branch of a bank (like Royal Bank of Scotland) and then tells the States its account has been duly credited.

The circulation begins. The States settles its obligations with those it has contracted to supply services, with its employees and so forth. Not all of these transactions are in hard cash, of course, But the accounts of these counterparts are credited in pounds. And cash withdrawals against these accounts by individuals and companies will also be in pounds.

Round and round it all goes. Every so often fresh pounds are required, but more importantly not all of the notes and coins survive within the island. Some are lost, some perish, and tourists lap them up. If you look at the States accounts, one page tells you all about the Note Issue.

During 2016, some £96.5 million in notes and coin was issued, and £94 million withdrawn. Some £42.4 million was circulating in notes, another £4.7 million in coins. These are not small numbers, and suggest that it is pretty useful for the States to be issuing its own currency.

This is because every Guernsey coin popped into a vending machine on the mainland, and the many notes which find their way outside the island, in effect reduce the States obligations and are thus a source of revenue. This does not include those notes “traded in” for sterling at FX boutiques and banks and despatched back to the island – a transfer which occurs under a generous convention with the UK.

Whether or not the reduction in States obligations is profitable depends on the costs of manufacturing the currency in the first place, transporting it to Guernsey, storing it securely before it is issued, and policing both its use and, er, misuse (meaning forgeries). These are not small costs. And don’t forget, the States Treasurer signs the notes. Over the past 25 years or so this office has been occupied by at least four individuals. A fresh ego-boosting print run is required each time.

Some people quietly wonder whether, one day, the island will find that it is not worth circulating its own currency. This is a bigger question than you realise. The simple economics may be less compelling than they were, but the psychic value far outweighs the commercial one. The Guernsey £1 note, in particular, is an important and much-loved symbol of the autonomous semi-sovereign standing of the island as a Crown Dependency, with responsibility for its own affairs outside defence and foreign relations. We are not the Isle of Wight…

A more dangerous threat to our notes, however, is the possibility that those using them choose no longer to do so. Look at the rapid increase in electronic transactions and you get the picture. The more serious worry on this front is that some sort of crisis over the island’s status prompts a loss of confidence in the government and a loss of trust in the currency.

There is no sign of this happening, but it is not uncommon elsewhere. All currencies these days are in effect “con tricks”, and Guernsey’s is no exception. Everyone is happy as long as they don’t think too hard about what is going on. That is why such scepticism persists over “bitcoin” and similar digital currencies, especially as their selling point is precisely that they have no ultimate backer.

It might be better to imagine Guernsey’s currency as a bit like its stamp issues – something which, incidentally, it conducts regularly. Every stamp which goes into collectors’ hands or is not used is a stamp which has been paid for. For each issue, Guernsey accounts for the reduction in circulation as a profit in its books. As with the currency.

So what is a Guernsey £1 note worth? The short answer is the same as £1 sterling. The exchange rate is fixed at 1:1, and no one questions the solidity of the rate. Whether a Guernsey pound has the same purchasing power as a sterling pound is another matter, but the truth is that no one worries about it. Guernsey is simply regarded as a more expensive place than the UK.

If the exchange rate floated, however…