When it rains it pours. We have just surfaced from an existential argument over assisted dying. We have a second one beginning over a proposed 20-point (20!) ten-year economic growth strategy. And, in between, rising tempers over a third issue: nothing less than the very status of our island as a Crown Dependency.

The last of these has arisen following an attempt by MPs in the House of Commons to force the Crown Dependencies and the Overseas Territories to have a publicly open register of beneficial ownership for the many thousands of companies and trusts they administer.

The Crown Dependencies, unlike the Overseas Territories, successfully blocked the move thanks to swift and strong island intervention plus crucial support from key figures in the UK government. A few days later, senior politician Deputy Gavin St Pier declared that now was the time for the islands’ leaders to put their heads above the parapet and make their views known.

It seems unlikely that many expected him to go as far as he has. But at a cleverly-timed seminar on Guernsey’s constitutional status, and in a statement before the States assembly, he reminded Deputies (and, pointedly, the world’s press awaiting the main debate on assisted dying) of Guernsey’s long history, going back well before the formation of the United Kingdom.

Towards the end of his lengthy peroration, he made the following statement:

“The Policy & Resources Committee believes it is of strategic importance that we have the legislative and procedural architecture in place to be able to test the will of the people of the Bailiwick – should it ever be necessary. In the event of any breach of constitutional convention by the UK, it is conceivable that the people of the Bailiwick may wish to express a view on the future constitutional relationship. I have already written to the Ministry of Justice to advise that we intend to progress this work as a priority…”

Given that we will be having our first-ever referendum (on island-wide voting) this October, it is not hard to interpret this statement as a threat to capitalise on the precedent and use the mechanism for a later referendum on the island’s future relationship with the UK.

This begs a classic “What if?” question. If the conventions which operate between Guernsey and the UK are broken, and if a referendum produces a demand for a change in the existing relationship, and if the UK seeks to flout this opinion, the States may feel entitled to declare independence unilaterally – a UDI.

No doubt this is an over-interpretation of what might happen, but it will not escape the attention of politicians and officials on both sides of the Channel. And it is hardly an over-interpretation if you think about past events in Rhodesia, Anguilla and the Falklands, and what might happen in Northern Ireland or Scotland because of Brexit.

At this point, such a prospect looks ridiculous. Deputy St Pier himself has suggested that one relatively simple reform Guernsey might seek is to have the Lt Governor sign off Royal Assent to legislation rather than the Privy Council. Perhaps, therefore, his statement is simply a warning shot across the UK’s bows. Perhaps, too, he won’t have the full support of the States itself to proceed. Still, you can’t help but wonder what the Lt Governor, the Bailiff and Law Officers make of his plans.

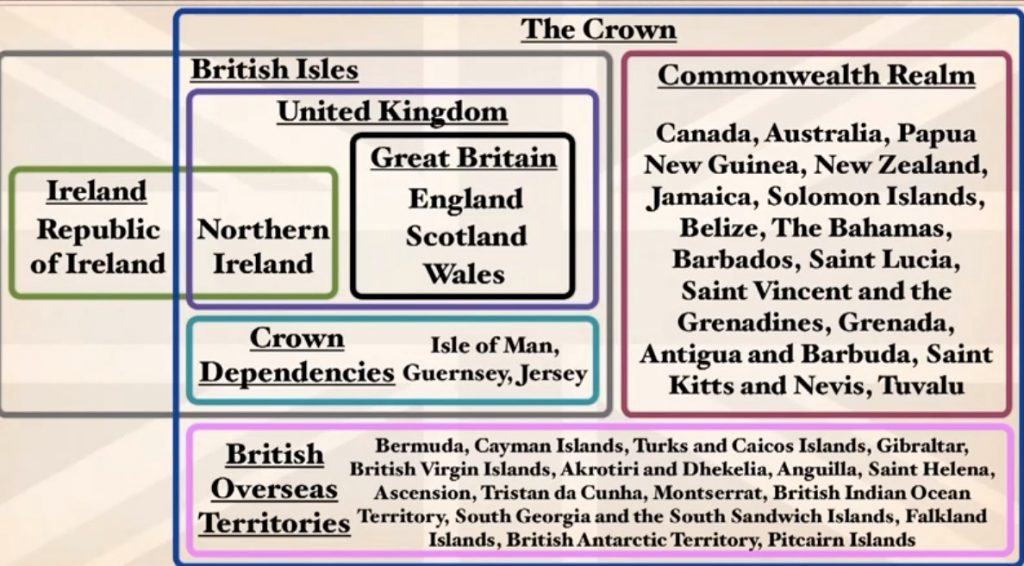

To understand the complexities of all this is a tall order, because the nuances are endless. Suffice to say, the conventions between the UK and the Crown Dependencies give the UK responsibility for the Dependencies’ defence and foreign affairs and, in a broader and vaguer sense, their “good governance”. In practice the UK does not legislate for the Dependencies without their consent.

To see how this has evolved in recent times, go back twenty years to the arrival of Tony Blair’s Labour party in power. The new government ordered an inquiry led by Andrew Edwards into financial regulation in the Channel Islands. The reaction in Guernsey was considerable irritation at an unwarranted and perhaps unprecedented intervention in Guernsey’s domestic affairs.

Although the inquiry outcome was favourable for the island, a lot of water has since passed under the constitutional bridge, as this sample list shows:

- A steady tightening in finance sector regulatory standards in the Crown Dependencies, attributable in part to a States commitment at the time of the Edwards report but also undoubtedly in response to steadily intensifying pressures from abroad, including the UK.

- Major alterations to the domestic tax regime as a direct result of pressure from the EU and the OECD, pressure which persists to this day.

- Two wholesale changes to Guernsey’s system of government, the first following a report by lawyer Peter Harwood, the second in response to recommendations from a committee headed by Deputy Matt Fallaize.

- A further inquiry, ordered by the Labour government and headed by Michael Foot, which in 2009 confirmed Guernsey to be a favourable, compliant and transparent international financial centre providing economic benefit to the UK.

- Two major domestic inquiries into our constitutional relationship with the UK, one by a Constitutional Advisory Panel established in 2008, the other by a Constitutional Investigation Committee set up in 2013. Neither, in the end, pressed for radical change.

- Dispensation granted by the UK, notwithstanding its responsibility for the island’s foreign affairs, for Guernsey to negotiate tax information exchange agreements with other jurisdictions and to establish an office in Brussels shared with Jersey to make direct representations to the EU.

- Investigations into aspects of Guernsey’s governance by outside bodies such as the Welsh Audit Office in 2007 and Tribal Helm in 2009.

- Continued interventions by backbench MPs in House of Commons debates relating to the Crown Dependencies, egged on by the leaks of the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers and the campaigns by anti-tax avoidance groups such as the Tax Justice Network

Given all this, local reaction to the latest intervention from backbenchers – led by Andrew Mitchell, a Conservative, and Margaret Hodge, from Labour – is hardly a surprise. And it has not come just from politicians like Deputy St Pier. The Guernsey Press has quickly editorialised twice on the subject. The current head of the Chamber of Commerce, Martyn Dorey – son of a former Bailiff – reacted at its annual dinner by saying: “We need a Plan B. We must be prepared to be independent. A lot people here see themselves as Anglo-Norman, not British.” He went on to urge investigations into a quasi-federal relationship with Jersey.

Deputy St Pier clearly has an eye to the possibility of another Labour government being elected, and wants to secure the option of a referendum while Guernsey has understanding friends in the current UK government – a plan for the worst, in other words.

Back in 1998, when Mr Blair ordered the Edwards inquiry, it required some wise advice from the Lt Governor to discourage a stroppy response from angered locals. Welcome the inquiry, he suggested, and demonstrate yourselves to be above board. That is what came to pass. But for many in Guernsey, rightly or wrongly, what has since occurred has the feeling of a slippery slope.

What, then, can we draw from this? Perhaps the 2016 Brexit referendum offers a clue. Voters who one day face a choice over Guernsey’s status will have to weigh their long-term economic interests against their sense of international self-importance. If they believe full autonomy will not guarantee political and economic security, negotiating a slippery slope will probably look safer than leaping into the unknown.